Author: Ornicha Daorueng, research intern

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer recently warned that the UK is at risk of becoming an “island of strangers,” attributing this to high levels of immigration and proposing stricter immigration policies. His remarks have drawn criticism, with some comparing them to the divisive and racially charged rhetoric of Conservative MP Enoch Powell’s 1968 “Rivers of Blood” speech, in which Powell claimed immigrants had made Britons feel like “strangers in their own country,” fuelling widespread anti-immigrant sentiment. Critics suggest Starmer’s comments may be politically motivated, reacting to Labour’s electoral losses to Reform UK, a party advocating tighter immigration controls. At the same time, Starmer’s stance can also be seen as a genuine attempt to address the challenges of integrating native and immigrant communities while maintaining social cohesion. However, rather than focusing solely on political motives, it is more productive to examine what Starmer means by “an island of strangers,” assess whether this is a fair characterisation, and explore how the UK can bridge the gap between communities and transform those whom Starmer described as strangers into fellow citizens.

The role of bonding social capital in immigrant life

Aristotle asserted that “man is, by nature, a political animal,” highlighting humanity’s inherent need for social connection to survive and thrive. Modern neuroscience affirms this: our brains are wired for social bonding. To fulfil this need, people gravitate toward communities that share familiar identities which offer belonging, trust, and mutual support.

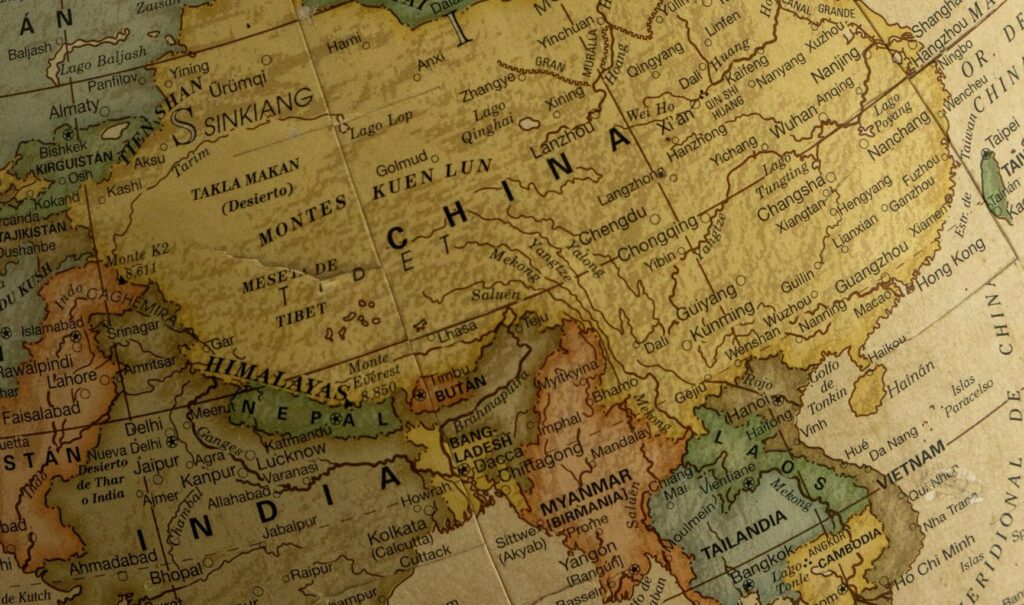

This is particularly evident among immigrant communities. Regardless of their origin, newcomers often face challenges such as unfamiliar cultures, languages, and social systems, which can cause feelings of alienation and insecurity. In response, they form strong bonds with those who share their national, ethnic, linguistic, or religious backgrounds. This strong attachment to inherited identities of “people like us” is known as bonding social capital. These networks help them adjust to new lives by offering social support, legal assistance, employment guidance, and housing, creating close-knit networks across major UK cities. For example, in the West Midlands, Pakistani migrant men gather in mosques and gyms, creating social spaces that reinforce cultural norms and mutual support. In East London’s Brick Lane, known as “Banglatown,” Bangladeshi-owned shops, restaurants, and the Brick Lane Mosque serve as communal hubs, preserving cultural identity while helping newcomers navigate life in their new country.

Why can too much bonding social capital make us strangers?

While bonding social capital offers essential support, it can also deepen divides between immigrant communities and wider society. When individuals primarily interact within their own cultural or religious groups, “us vs. them” mentality can develop. A case in point is the Bangladeshi community’s “Save Brick Lane” campaign, which opposed gentrification and framed hipsters, startups, and investors as cultural threats. Such insularity reduces dialogue, reinforces confirmation bias, and fosters rigid group norms. Moreover, strong alignment with inherited identities can weaken connections to the host country. For instance, 71% of British Muslims identify primarily as Muslim, compared to 27% who identify as British. This disparity can contribute to feelings of alienation, particularly when national policies conflict with religious or political beliefs.

Religious identity may also be linked to authoritarian tendencies. Studies show that Christian and Muslim respondents are more likely to hold socially authoritarian attitudes, valuing order, conformity, and group loyalty. These tendencies can hinder integration and increase vulnerability to populist leaders who promise protection for their group, an important factor that can contribute to the emergence of extremism.

Bonding social capital, when unchecked, can create various forms of “strangeness”: between different immigrant communities, between immigrant communities and the wider British society, and even in the perceptions British citizens hold toward immigrants. Public opinion reflects this divide, with 52% of British citizens supporting reduced immigration and only 14% favouring an increase. This suggests a disconnect between wider society and immigrant communities, which helps explain what Sir Keir Starmer meant by the UK becoming an “island of strangers.”

From strangers to acquaintances: the power of bridging capital

In contrast to bonding, bridging social capital connects people across diverse social groups. These connections are typically based on shared interests or acquired identities, such as education, professions, or hobbies, rather than ethnicity or religion. For migrants, this expansion of social circles is vital to integration and developing a sense of belonging that is rooted in Britishness, rather than the narrow confines of religion or ethnicity.

Successful integration is often driven by economic and educational advancement, providing more pathways for migrants to foster bridging social capital. The Indian diaspora in the UK exemplifies this. With the highest levels of education, a strong presence in professional occupations, and the highest homeownership rates among ethnic groups, Indian migrants exemplify how education leads to professional advancement and ultimately, economic stability. This socio-economic trajectory enables greater connection with broader society, helping many see the UK as their true home.

Communities worldwide have successfully implemented grassroots initiatives to support socio-economic integration. In education, Sweden’s Fryshuset youth organisation creates inclusive spaces through music, sports, and cultural activities, allowing young people to connect beyond ethnic lines. The state-funded SFI program also offers free, flexible language courses to adult immigrants, helping them navigate society and improve their employment prospects. In the economic front, Canada’s TRIEC collaborates with private, public, and non-profit sectors to foster inclusive hiring practices while helping migrants expand their professional networks and understand the local labour market. In the Netherlands, Qredits supports migrant entrepreneurs through business training and microloans. For civic engagement, Australia’s Stronger Communities Programme funds grassroots organisations and local councils to strengthen community ties and promote social cohesion. These examples show that bridging social circles does not require grand policies; it often begins with simple acts at the grassroots level. This is where the UK has room to learn and invest.

Returning to the question, “Is the UK becoming an island of strangers?” The answer is yes, but not because of who is arriving. It is because we are failing to build shared spaces of connection: in schools, workplaces, neighbourhoods, and civic life. By rebuilding socio-economic bridges, we can help migrants move beyond the confines of close-knit communities, gain meaningful exposure to wider British society, and begin to find their identities in relation to the country where they are building their lives in. In doing so, we help migrants feel at home, and just as importantly, help the broader British public, including White Britons, feel confident in welcoming others into a shared home. Only then can we turn strangers into acquaintances, and acquaintances into fellow citizens.