Author: Niharika Girsa, research intern

Every time you ask an AI chatbot a question, you might be using more water than you did for your morning coffee or tea. AI, born from human intelligence, represents the next great leap in human innovation since the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution. Unlike those earlier advancements, which focused on reforming tools and processes, AI mimics the way the human brain works, it learns from experience, evolves with new data, and improves through training.

Studies from University of Colorado and University of Texas at Arlington has estimated that each ChatGPT session-comprising roughly 20-50 prompts consume the equivalent of a 500 ml bottle of water, used primarily to cool the data centres. Globally training large models like GPT-3 has been shown to consume over 700,000 liters per cycle. While exact national figures are unavailable, if we extrapolate based on India’s growing digital user base it is plausible to say that the country’s AI driven infrastructure could pose significant water demands. On average, a 1-megawatt data centre consumes around 26 million liters of water annually. And with India’s current capacity at approximately 1,255 MW, the cumulative annual water consumption across existing facilities alone could exceed 32.6 billion liters per year.

In a nation where over 600 million people are already facing high to extreme water stress, this is more than just a hidden cost, rather it is a Wake-Up call. The water footprint of our digital lives is becoming increasingly visible, and that’s a good thing. As AI becomes embedded in everything we do, it presents us with a powerful opportunity: to not only harness its potential, but to design it responsibly. Now is the moment to ask not just what AI can do for us, but how we can ensure it gives back more than it takes.

HOW IT WORKS?

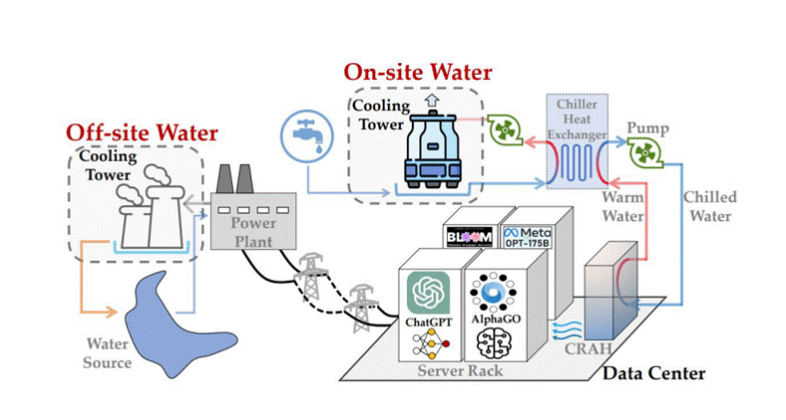

Every chatbot response or AI-generated picture conceals a physical space, a data centre, buzzing with computers fuelling these technologies. Often hidden within large warehouses, these facilities operate continuously 24 hours a day, using significant quantities of power to remain cool and run smoothly. AI learns, stores, and gets smarter every day in these climate-controlled centres.

Although generative AI operates virtually and holds great potential, it has consequential real-world impacts. Servers are doing hundreds of calculations to produce the best feasible response and process every prompt sent to a generative artificial intelligence model. Located in data centres, these servers generate significant heat during processing. Often, water cooling devices are used to avoid overheating. Much like the human body utilises sweat to control temperature, these systems move the heat to cooling towers, where it is expelled from the data centre.

A study by the University of California Riverside and the University of Texas Arlington has uncovered the water consumption linked with AI models, termed the “secret water footprint.” Dr. Venkatesh Uddameri, a leading water resources expert from Texas, points out that a single data centre can consume between 11 and 19 million litres of water each day, roughly matching the daily water needs of a town of 30,000 to 50,000 residents.

The researchers also calculated that training GPT-3 in Microsoft’s US data centres can directly consume 700,000 liters of freshwater, which is equivalent to what it takes to produce 370 BMW cars or 320 Tesla electric vehicles. And if this training were to take place in the company’s Asian data centres, the water consumption would have tripled. This is because, unlike temperate regions where data centres can often rely on “free” cooling by using outside air to reject heat, many parts of Asia experience consistently hot and/or dry climates. When the outside air temperature exceeds 85 degrees Fahrenheit or the air is too dry, data centres must rely on water-based cooling methods. Water is needed both for evaporative cooling and for maintaining proper humidity levels. As a result, the climate conditions in Asian regions substantially increase water demand, leading to significantly higher consumption during AI training operations.

While the environmental footprint of AI is a global concern, its impact is particularly striking when we look at individual countries. As data centre expansion accelerates in countries like the United Kingdom, and India grapples with acute water scarcity amid rapid digital growth, the hidden “water cost” of the AI revolution has become an urgent issue.

The United Kingdom is positioning itself as a future global leader in artificial intelligence, pouring investment into new data centres to drive advances across sectors from healthcare to financial services. However, this digital expansion carries a hidden environmental cost: a growing strain on the country’s water resources.

Recent reporting by The Guardian highlights that new AI growth hubs are being proposed in areas such as Culham, Oxfordshire, which are close to the site of a major planned reservoir intended to secure long-term water supplies for London and surrounding counties. Data centres, particularly those supporting AI workloads, require vast amounts of water to cool servers that run non-stop. A single large data centre can consume between 11 and 19 million litres of water daily comparable to the water needs of a town of 30,000 to 50,000 people.

Although the UK benefits from a relatively wet climate compared to other parts of the world, it is not immune to droughts and growing regional water stress. Environmental groups are increasingly voicing concerns that the surge in data centre development risks outpacing infrastructure improvements, putting ecosystems and community water supplies under pressure.

While the United Kingdom faces mounting concerns over the environmental costs of its AI-driven digital expansion, India’s situation is even more critical. India, one of the fastest-growing digital economies in the world, is quickly expanding its artificial intelligence capacity as demand for cloud computing and AI-powered devices rise. The country’s data centre capacity is projected to grow exponentially, with estimates suggesting it will reach 3,400 MW by 2030, driven by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21% from the first half of 2024.

Cities like Bengaluru are already facing acute water shortages, which house massive data centres that consume millions of litres of water daily for cooling. According to a report by Lawfare, Bengaluru’s data centres currently consume an estimated 8 million litres of water per day, contributing to the city’s water scarcity issues.

Without urgent policy interventions and sustainable technological innovations, India’s AI ambitions could come at an unsustainable environmental price, undermining the very progress it seeks to achieve. Despite the rapid growth of India’s data centre industry, there is a notable absence of national policies addressing the water usage of these facilities. The draft National Data Centre Policy 2020 encourages the use of renewable energy sources but does not mandate them, and it fails to address the critical issue of water consumption. This oversight raises concerns about the long-term environmental impact of India’s expanding digital infrastructure.

As AI continues its rapid global expansion, its hidden water footprint is placing immense pressure on already strained resources, particularly in countries like the UK and India. In the UK, while data centres are now classified as critical infrastructure, there is still a lack of specific regulation on water usage. The country must prioritise sustainable cooling technologies and avoid siting new centres in water-stressed regions. In India, where water scarcity is acute in certain regions and digital growth is accelerating, the current National Data Centre Policy overlooks water usage entirely. Both nations must urgently implement clear policies mandating water and energy use disclosures, while aligning digital infrastructure development with long-term ecological resilience. Without immediate actions the invisible cost of AI’s growth will be paid in the most important currency of all – Water, and by those least equipped to bear it.