The UK is a representative democracy. At the UK-wide level, decisions are made by a parliament which is elected around once every five years. However, in the 2010s the UK experimented with referenda (when the public are asked directly on a specific issue) to inform decision-making. There were three major referenda in this period:

|

Date |

Question |

Turnout |

Result |

|

2011 |

“At present the UK uses the “first past the post” system to elect MPs to the House of Commons. Should the “alternative vote” system be used instead?” |

42.2% |

Yes: 32.1% No: 67.9% |

|

2012 |

“Should Scotland be an independent country” |

84.6% |

Yes: 44.7% No: 55.3% |

|

2016 |

“Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? |

72.2% |

Remain: 48.1% Leave: 51.9% |

However, in the 2020s referenda are no longer popular. This is a problem as, by association, discussions about more direct democratic participation have been abandoned. Due to this spillover effect, it is important to once again discuss referenda in the context of strengthening British democracy.

Issues that emerged

To have this discussion within the policy and research space, it is important to understand three principal issues that emerged from the experiments.

- What does a ‘once in a generation vote’ mean?

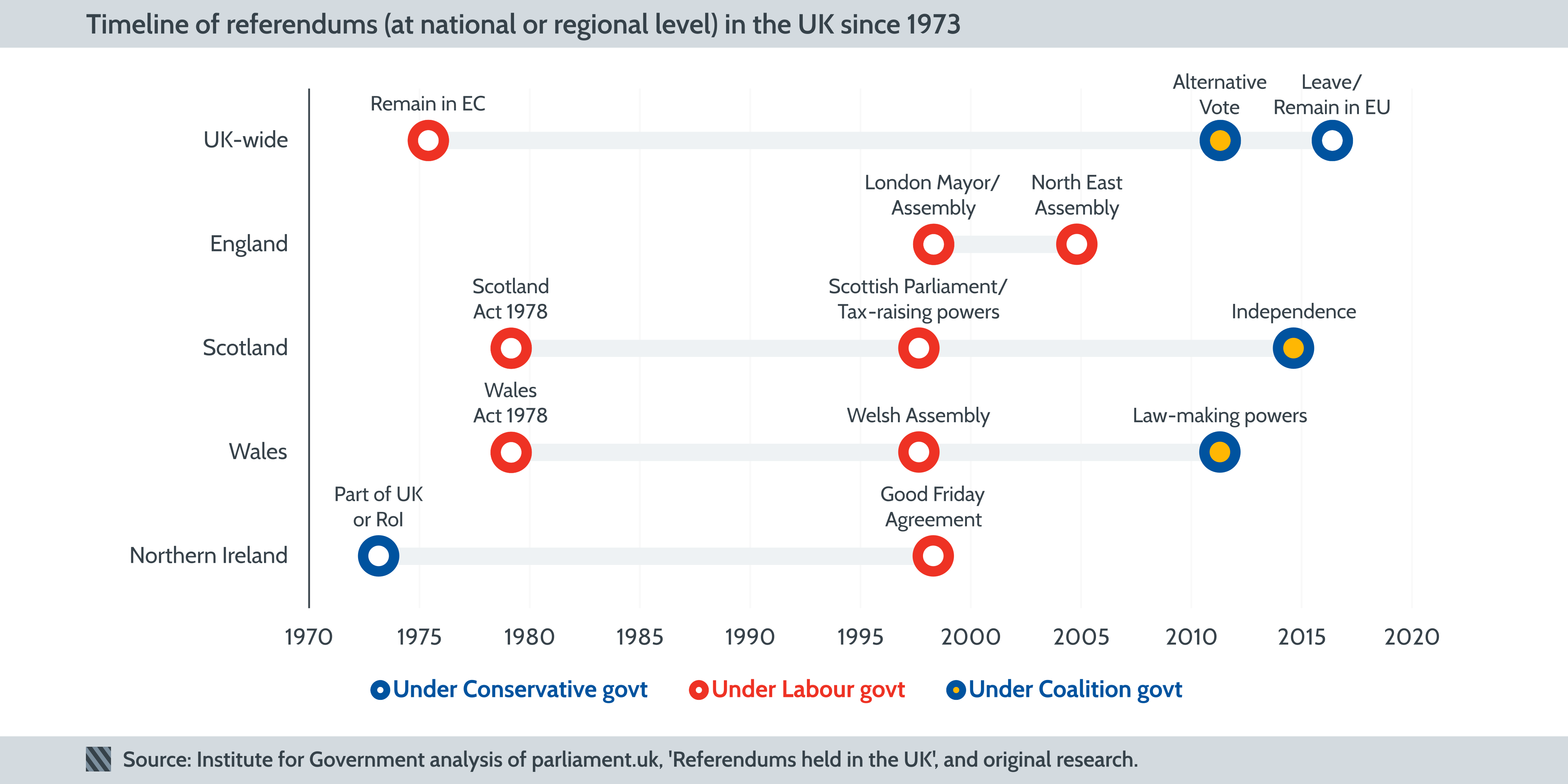

The Alternative Vote (AV), Scottish independence and EU referendum campaigns all claimed that they were an attempt to settle their issue ‘for a generation’. But how does one define a generation? The number usually brought up was once every 20 years (the gap between each of the 1979, 1998 and 2014 Scottish referenda). However, there is no legal requirement for the gap to be so long. The Northern Ireland Act allows a seven-year gap between secession referenda. This is an issue that remains unresolved, with the UK having no general procedure for enacting a referendum. Therefore, there was no agreement about the frequency with which they should be a part of the democratic process.

- What subject-matter warrants a referendum?

Linked to this, there was also confusion about what issues warrant holding a referendum. There was some consensus since the 1990s that referendums should be held on questions of devolution, but even that was fairly weak. For example, in 2011 there was a referendum to grant Wales more devolved powers but later it was decided that the Welsh Assembly could be given income tax powers without a referendum. This was also seen with the Brexit process as neither the Maastricht Treaty nor the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement were directly taken to the public. However, instead of having discussion about what requires the direct consultation of voters, the UK has simply returned to the default of representative decision-making.

- Referenda refused to silence the debates on the issues they sought to address

Given that all these referenda were on divisive issues, it is not surprising that the ‘loosing camps’ continued to remain vocal following the results. Despite losing the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum the Scottish National Party continues to be a political force, having won two more elections in Holyrood whilst repeatedly calling for a second referendum. This was also seen through the People’s Vote campaign following the 2016 EU referendum. Six million people signed a petition to rejoin the EU and hundreds of thousands attended a march calling for a second vote. That they were incapable of silencing these issues reveals problems with the binary nature of these referenda. All three of the referenda were anti-pluralist, turning complicated issues into binary questions with the ‘winner’ simply needing over 50%. Given the controversy of the issues this was not a fair way of representing the plurality of opinions that the public had. However, at no point were different forms of referenda (such as including more than two options) seriously considered as a solution for the future.

It is important to acknowledge these issues as the questions they raise are still as relevant as they were in the 2010s. These include questions such as when decisions require direct consultation of voters and how best to reflect the plurality of their opinions. Having these discussions is essential for strengthening democracy in the UK.

Why do we need to discuss referenda?

It is important to discuss these in relation to referenda because they are not dead. The 2010s were not an isolated experiment but instead a ‘third wave’; the first started with the Northern Ireland border poll in 1973 and ended with the Scottish devolution referendum in 1979, and the second occurred between 1998 and 2004 around the creation of devolved assemblies in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, Greater London and North East England (the last of which was overwhelmingly rejected). Therefore, referenda are simply dormant and there is no reason they could not become popular again. Policy discussion therefore must take referenda seriously lest the same mistakes are made again.

It is also important to have this discussion because it involves looking outside of Westminster. Devolved and local authorities provide opportunities for experimenting with different forms of democratic participation. This is seen at the moment with the use of citizens assemblies or digital democracy. At the local level there have been important referenda following Brexit such as Bristol voting in 2022 to abolish elected mayors. These examples can provide us with a great opportunity for providing greater insight into the potential role of different forms of democratic participation.

However, Parliament has not published a report of referenda in local authorities since 2016. This is an apt metaphor for the reluctance of policymakers to continue engaging with the advantages and disadvantages of referenda, even though there are still many discussions to have. The responsibility of this should be taken up by think-tanks and researchers. If research communities take referenda seriously, both other researchers and policymakers can have a better understanding of their merits and drawbacks. This will lead to far more constructive discussions about the nature of democratic representation in the UK and the role that more direct forms of decision making can have in the country’s future.

Through this combination of experiments at the local level and research communities reengaging with referenda, we can restart the discussion on democratic representation in the UK. Following on from this there are two further avenues for exploration which should be considered:

- There needs to be a dialogue amongst fellow research communities about the lessons learnt from the referenda of the 2010s and how they might shape referendum practice in the UK going forward.

- Local authorities should continue experimenting with referenda as well as other forms of democratic participation to better understand their potential uses and limitations.