India’s renewable energy (RE) transition is no longer just about ambition, but momentum. In the first half of 2025 alone, the country added a record 22 gigawatts (GW) of RE capacity, the highest six-month addition in its history. Solar and wind dominated the surge, driven significantly by government waivers on interstate transmission charges. While this reflects growing traction across both public and private sectors, its unprecedented scale does however bring its own challenges. For India to achieve its 2030 targets, it will require an estimated $233 billion in investment for solar and wind alone. Although international capital has been instrumental in financing RE projects to date, over half of India’s project debt continues to originate from foreign lenders, leaving developers vulnerable to currency fluctuations and shifts in global risk appetite. Whilst domestic public finance isn’t absent, it isn’t leading either and remains limited relative to private and external sources. If India is to develop more resilient RE systems, the public sector will need to play a more enabling role – not by spending more, but by unlocking deeper domestic capital flows that support long-term transition goals.

Why Public Capital Isn’t Leading

The Indian state faces a score of competing fiscal obligations; healthcare, food security, social protection, and infrastructure each lay claim to scarce budget capacity and whilst climate-related spending is increasing, by all accounts it still only forms a relatively small proportion of total public expenditure. Less than 10% of total public energy subsidies were allocated to clean energy initiatives in 2023, for instance. Fragmentation across ministries, states, and regulatory bodies further dilutes strategic focus, while bureaucratic inertia and low risk tolerance reduce appetite for innovative financial instruments. Whilst mechanisms such as credit guarantees and viability gap funding for instance, do exist, but are often limited in scope or implementation.

Meanwhile, India’s clean RE project pipeline – though expanding – is undercapitalised and spatially uneven. High financing costs, especially outside high-priority regions, remain a persistent barrier and while RE capacity has grown rapidly, usage hasn’t kept pace; non-renewable sources still form over 64% of the country’s operating power capacity and another 30,0000 megawatts (MW) of coal-based capacity is in the pipeline. Rather than steering the transition, public finance has been reactive, failing to provide the early-stage risk cover or downstream signals needed to unlock institutional capital at scale. Addressing these gaps requires more than additional funding. It calls for financing models that better share risk and crowds in private capital at scale.

The Case for Blended Finance

India’s clean energy transition doesn’t just hinge on how much capital is available but on the kinds of risk it can absorb. Despite India ranking among the world’s most attractive emerging markets for clean energy investment, borrowing costs in such developing countries reach up to three times those in advanced economies, meaning even commercially viable projects often struggle to access affordable, long-term finance. The underlying challenge is structural; currency volatility, uneven infrastructure, and shallow domestic debt markets create a risk environment that deters institutional capital from investing at scale, particularly in early-stage technologies and emerging regions.

This is where blended finance has begun to show promise. By using public or concessional capital to take on subordinated risk, governments can shift the risk-reward balance enough to draw in private investors, especially in nascent or underserved sectors; mechanisms including first-loss guarantees, subordinated equity and concessional loans could facilitate this. In India, interventions have already demonstrated how layered capital structures can help reduce tariffs, crowd in institutional players, and accelerate adoption in sectors that otherwise struggle to scale.

Case Studies: The NIIF and Simpa Energy

India’s preliminary experiences with blended finance offer a useful insight into what catalytic public capital can unlock and where it still falls short. In partnership with the UK government and the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund – India’s flagship sovereign-backed platform – launched the Green Growth Equity Fund (GGEF) in 2021. As a $944.5 million RE platform that combines public equity with concessional GCF capital, it crowds in global pension and sovereign wealth funds, enabling risk-sharing across solar and wind projects, supporting lower tariffs in auctions, and attracting commercial co-investors, particularly into utility-scale projects. Whilst successful, its reach remains limited; smaller developers, early-stage technologies, and underserved regions still face significant barriers.

Such models thus demand institutional replication and localised implementation. The case of Simpa Energy India offers a complementary model. With a $6 million concessional loan from the Clean Technology Fund, administered by the Asian Development Bank, Simpa was able to expand its off-grid solar home systems across rural India. The approach lowered the cost of entry for households, enabling repayment through electricity bills and recovery of installation costs within 1-2 years. The outcome provided a commercially viable business model that delivered green development co-benefits without relying on grid infrastructure, resulting in its acquisition by energy services group, ENGIE.

Blended finance has proven versatile, supporting both large-scale utility infrastructure and decentralised solutions. Yet its application remains mostly tactical, concentrated at the project level. To unlock its full potential, the focus must shift toward system-wide transformation—using blended structures not only to bridge financing gaps but also to align with national climate and industrial strategies, mobilise domestic capital, and establish long-term investment pipelines where public capacity is weakest. Without this shift, even successful one-off interventions will struggle to change underlying risk dynamics or build scalable markets.

How to scale the transition from Projects to Systems

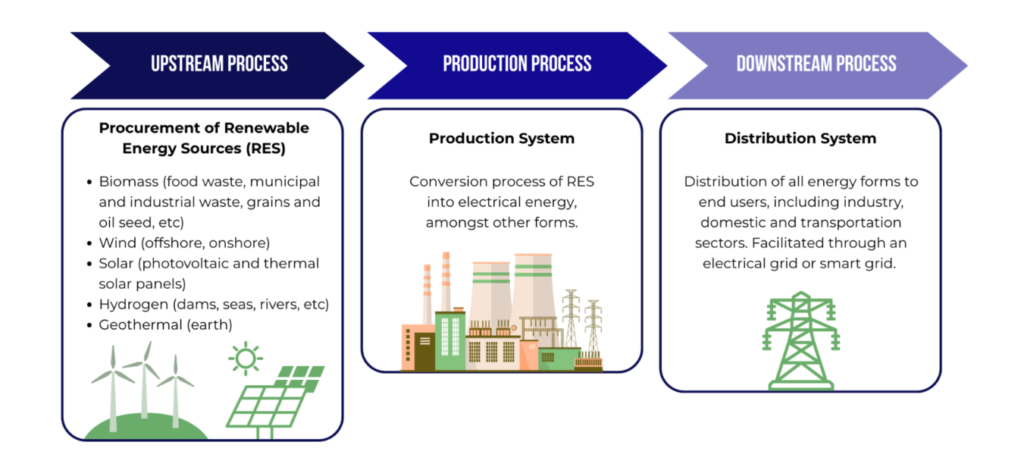

India’s next challenge lies in designing frameworks that embed projects within institutional ecosystems. Strengthening financial institutions like the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency will be key, utilising blended capital to expand affordable lending across states. Similarly, fund-of-funds platforms that pool risk and enable aggregation can provide impetus, particularly for smaller initiatives such as rooftop solar or rural mini-grids. Central and state government must also look beyond generation to de-risk upstream and downstream assets, ensuring system-wide transformation across the renewable energy supply chain. Bankable development of manufacturing, transport logistics (ports, road/rail and heavy-lift handling for blades, towers and panels), transmission infrastructure (pylons, high-voltage corridors and substations), and end-of-life recycling can be unlocked through the strategic deployment of blended finance instruments. Disbursements tied to policy performance through results-based financing models can effectively reward regulatory clarity and incentivise consistent implementation across such verticals.

In short, blended finance isn’t just about what we build but shaping the systems that make RE viable at scale.

Complementary Instruments

Whilst blended finance will be vital to the transition, it is not, however, a silver bullet; its effectiveness depends on the system-wide implementation of complementary instruments. Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) for instance, are widely endorsed to share technical and delivery risks in storage, green hydrogen, and smart grids. Similarly, green bonds, especially those with transition-linked KPIs, can attract climate-conscious institutional investors. Sovereign-backed green strategic investment vehicles could also play a role, whether through NIIF expansion or a new green sovereign fund, anchoring investment for dynamic projects. These mechanisms must be reinforced with regulatory reforms to further de-risk the investment environment; this could include enabling sub-sovereign borrowing, enhancing enforcement of power purchase agreements, and standardising ESG disclosures.

Together, these tools can provide the financial architecture needed to enable blended capital to operate at scale, within a transparent, rules-based system.

Steering the Transition, Strategically and Fairly

India’s public sector doesn’t need to fund the energy transition alone, but it must be strategic in how it leads. Blended finance provides the levers to unlock private investment and embed resilience in India’s climate finance architecture. But this requires systems thinking and institutional coherence.

It also demands intention. The transition is not only about shifting energy systems, but about ensuring that this shift is fair, recognising the social, geographical and economic realities that shape energy access, employment, and equity across regions. Blended finance, done right, can embed such equitable practice within the architecture of transformation; by absorbing risk at the margins, directing capital to underserved regions, and supporting inclusive business models, it can neatly align with developmental outcomes.

Overall, the energy transition is more than a capital gap; it’s a governance challenge and a systems-building opportunity. The future of India’s clean energy story won’t be decided by how much public money is spent, but by how wisely it’s deployed.

References

Institutional Reports

International Finance Corporation. (2023). Blended finance for climate investments in India. https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/2023/Report-Blended-Finance-for-Climate-Investments-in-India.pdf

Modak, P., Robins, N., Tandon, S., Muller, S., Subramanian, S., & Curran, B. (2023). Just finance India: Mobilising investment for a just transition to net zero in India. British International Investment. https://justtransitionfinance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Just-Finance-India.pdf

Rosales, R. C., & Aikman, D. (2024). Mobilising finance for net zero energy systems: Key issues, barriers and policy priorities. King’s Business School. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/business/assets/PDF/research-papers/aikman-and-rosales-impact-policy-paper.pdf

Saboo, A., & Srivastava, S. (2022). Renewable energy financing landscape in India: The journey so far and the need of the hour. Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. https://ieefa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Renewable-Energy-Financing-Landscape-in-India_February-2022.pdf

Selvaraju, S. R., Robins, N., & Tandon, S. (2024). Sustainable finance for a just transition in India: the role of investors. Just Transition Finance Lab. https://justtransitionfinance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Sustainable-finance-for-a-just-transition-in-India-Role-of-investors.pdf

Vikas, N., Garg, V., Aiyer, S., & Srivastava, S. (2024). Blended finance: Key to bridging energy transition gap in developing countries. Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. https://ieefa.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/Blended%20finance%20key%20to%20bridging%20the%20energy%20gap%20in%20developing%20countries_Feb24.pdf

News and Web pages

Koshy, S., & Goyal, S. (2025, July 1). Blended finance: An idea whose time has come. Luthra and Luthra Law Offices India. https://www.mondaq.com/india/fund-finance/1653904/blended-finance-an-idea-whose-time-has-come#:~:text=Blended%20concessional%20finance%2C%20or%20blended,the%20Sustainable%20Development%20Goals%2C%20and

Randall, T., & Lankes, H-P. (2022, November 30). How can ‘blended finance’ help fund climate action and development goals. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/how-can-blended-finance-help-fund-climate-action-and-development-goals/#:~:text=The%20public%20or%20philanthropic%20capital,achieving%20climate%20goals%20and%20the

Sarkar, A., Gangahar, M., & Khurana, S. (2025, March 7). Transforming India’s climate finance through sector-specific financial institutions part 2. Climate Policy Initiative. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/transforming-indias-climate-finance-through-sector-specific-financial-institutions-2/#:~:text=As%20per%20Landscape%20of%20Green,requirement%20(CPI%2C%202024)

Seshadri, S. (2025, May 28). Blended finance can help power India’s climate future [Commentary]. Mongabay. https://india.mongabay.com/2025/05/blended-finance-can-help-power-indias-climate-future-commentary/#:~:text=Blended%20finance%20involves%20the%20use,efficiency%20in%20buildings%2C%20and%20more.