India lies at a crucial crossroads on its pathway to becoming a low-carbon economy. Over recent years, India has cemented itself as a leading climate player; in August 2022, it expanded its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets on GDP emission intensity under the Paris Agreement goals and according to the International Finance Corporation, remains the only G20 nation aligned with 2°C global warming targets. With this substantive progress, however, India resultantly lies at the heart of a financing gap, where over USD 2.5 trillion will be required to meet their updated commitments.

To realise the country’s 2070 Net Zero goal and broader Viksit Bharat 2047 (developed India) initiative, India must now “enhance the availability of capital for climate adaptation and mitigation”, leveraging channels of public and private capital both domestically and from international actors alike. A robust climate finance ecosystem must simultaneously act as an enabler, leveraging clarity and transparency in championing climate goals.

In this context, India’s draft Climate Finance Taxonomy framework represents a significant step forward. Published by the Department of Economic Affairs in May 2025, the framework seeks to facilitate greater resource flow to climate-friendly technologies and activities by formulating a methodology for identifying/classifying those that contribute to India’s climate commitments. In articulating what constitutes “climate-aligned”, it offers a rare chance for India to harness classifications to unlock finance at scale, especially if policymakers make design choices that link definitions to instruments, governance and performance measurement.

What the draft proposes

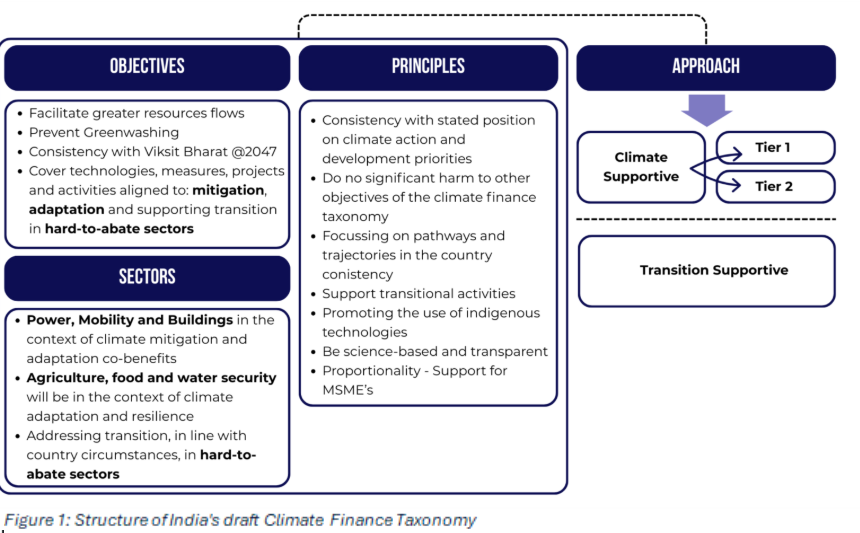

As figure 1 details, the draft frames climate-aligned activity across three distinct categories: mitigation, adaption and supporting transition for hard-to-abate sectors where eligibility is constrained. The framework follows eight principles to ensure credibility and impact. It aims to unlock capital, support innovation, and align investment with India’s Net Zero pathway, creating clear opportunities with preliminary sectoral coverage across clean energy, transport, building, and agriculture.

Under the implementation blueprint, India will reinforce the framework through a “hybrid approach”, first applying qualitative criteria to broadly identify climate-aligned activities. Over time, the taxonomy will adopt quantitative thresholds for example, specific emissions savings targets to make alignment measurable and auditable. The taxonomy classifies activities into two main categories in aiming to direct public and private investment toward credible, measurable, and impactful climate solutions across India’s economy:

- Climate-supportive activities: Includes projects that reduce emissions, deploy adaptation solutions, or contribute to climate goals through research and innovation:

- Tier 1 – activities directly avoiding emissions like renewable energy.

- Tier 2 – those that lower emissions intensity with clear pathways for improvement.

- Climate transition activities: Projects in sectors where low-emission alternatives are not yet viable. The taxonomy provides a pathway for these sectors to decarbonise over time without disrupting their economic function.

Crucially implementation is staggered, following the precedent of EU and ASEAN taxonomies. An initial phase focussed on qualitative criteria will be followed by the incorporation of numerical benchmarks for greater precision, with the framework acting as a living and dynamic document that adapts over time. Similarly, the framework incorporates specific provisions to ensure resource flows to agriculture and MSMEs aren’t adversely impacted, utilising simplified and proportionate criteria to address their resource constraints; this likewise recognises the diverse capacities within industrial organisations across sectors in India, allowing inclusivity and proportionality. This design dually preserves domestic flexibility but makes tightening predictable, thus enabling time-bound, target-driven transitional allowances for hard-to-abate sectors while protecting the taxonomy’s credibility.

Why a taxonomy is vital to mobilising capital

Current climate financing shortfalls in India – exacerbated by constrained domestic bank capacity, fragmented ESG practices, and widespread investor scepticism about green-washing – render the taxonomy as vital to credibly scaling capital. If effectively integrated alongside existing climate-related policy frameworks, a clear taxonomy could lower barriers and form bankable signals in three practical ways. First, it reduces transaction and due-diligence costs; investors and underwriters can use a shared classification to speed appraisal and standardise documentation across green bonds, project finance and blended-finance structures. Second, it leverages public capital to crowd in private investors; sovereign/sub-sovereign green bonds, concessional financing and first-loss/partial guarantees can all be tied to taxonomy alignment, reducing project risk and borrowing costs, whilst unlocking domestic finance and lending. Third, it builds investor confidence by reducing greenwashing risks; routine disclosure, public registries of labelled instruments, performance metrics tied to impact measurement and management reporting, and climate budget tagging. This allows capital providers to track outcomes through the financial system, ensuring fiscal pipelines are aligned to taxonomy-eligible projects.

Dynamic interoperability will be a crucial enabler. Mutual-recognition clauses with EU, ASEAN and Gulf taxonomies and clear interoperability rules will reduce repeated verification and legal friction, enhancing accessibility for Indian projects to cross-border and institutional investment from foreign asset managers, sovereign wealth funds and multilateral development banks. With this, however, global precedents highlight true potential: the EU taxonomy helped mobilise large green-bond flows, while ASEAN, Singapore and the UAE have used taxonomy-consistent instruments to attract cross-border capital. In short: design choices – linkage to instruments, measurable metrics, governance and interoperability—will determine whether the taxonomy simply describes “good” projects or actually unlocks the billions India needs for a just, bankable transition.

Limitations and Recommendations

The draft is an important step, but two structural weaknesses already stand out. First, it remains a high-level framework, missing enhanced detail on sectoral annexures and activity-level definitions. It also explicitly states that “coal-based power will continue to play a role in ensuring energy security, particularly for meeting base-load demand”; such allowances could be a concern, especially if fossil-linked sectors (steel, cement, power) continue lobbying for generous transitional definitions from this anchor point. Together these create an ambiguous signal that risks confusing investors and exacerbating pre-existing implementation challenges. However, these limitations are manageable if the next stage of public consultation is used effectively.

India must now also seek to maximise impact by prioritising adaptation finance, recognising that adaptation remains chronically under-funded despite recent momentum. The taxonomy should therefore explicitly ring-fence adaptation-eligible instruments to scale up bankable resilience projects. It should also be anchored within an Integrated National Finance Framework (INFF), serving as an eligibility rulebook for budget allocations, sovereign green bonds, and concessional finance, while simultaneously driving climate-budget tagging and medium-term fiscal planning so that climate priorities are deliberately resourced. At the same time, data and transparency gaps must be fixed; a central, standardised data registry would allow investors to track sustainability metrics, returns, and outcomes across eligible projects. Finally, alignment must be made binding rather than optional. To close the implementation gap and prevent stasis, taxonomy-alignment could become a condition for priority access to climate-finance instruments, with phased-in reporting obligations for banks and large corporates.

Conclusion

The taxonomy framework sensibly draws on global best practices while remaining grounded in India’s domestic realities. However, while its eight principles are well-rounded, more specificity is needed to evaluate their practical relevance and impact. Overall, the draft is a promising start but remains a nascent step toward mobilising the capital India needs; without fully developed sector annexures, robust reporting, and explicit links to finance instruments, investors will not receive bankable signals. As the draft enters public consultation, the Department of Economic Affairs and Ministry of Finance should prioritise these elements, otherwise the framework will remain a credible statement of intent rather than the market-making guide India requires.