India, the world’s most populous country, with 1.4 billion people, is facing a serious water crisis. It has 18% of the world’s population but just 4% of water resources, and 70% of the available water is contaminated. Moreover, by 2030, twenty-one major cities will run out of groundwater according to a study by NITI Aayog. Root causes are multifaceted, from over–exploitation of groundwater to poor rainwater harvesting, water mismanagement, pollution, inefficient irrigation, and legal and institutional challenges.

But the question is, what makes it a national security concern? Water is hardly ever part of National security discussions. National security is commonly understood as the ability of a country to protect its citizens, economy, and institutions from threats. So, national security discussions often revolve around border disputes, cyberattacks, terrorism, and other conventional security threats. However, the growing water crisis can significantly impact societal peace, regional stability, and strategic interests. It can further affect India’s economic trajectory and geopolitical standing, underscoring the link between water security and national security. This is especially concerning because India’s major river systems – Ganga, Indus, and Brahmaputra originate outside its borders in Tibet, which is under Chinese control. Thus, adding a layer of geopolitical complexity to India’s water challenges.

Water Scarcity and Mass Migration

Over 600 million Indians face high to extreme water stress, with 200,000 deaths annually due to inadequate safe drinking water. Water shortages are driving migration in the country. A study by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) revealed that water scarcity remains one of India’s primary reasons for migration. With 39.5% of employed people migrating from urban areas and staggering 67.5% from rural areas due to water shortage. NITI Aayog’s report projects that India’s water demand will double the available supply by 2030. This could potentially lead to mass migration and increased pressure on already overburdened urban infrastructure, creating internal instability.

Trigger for Conflict and Violence

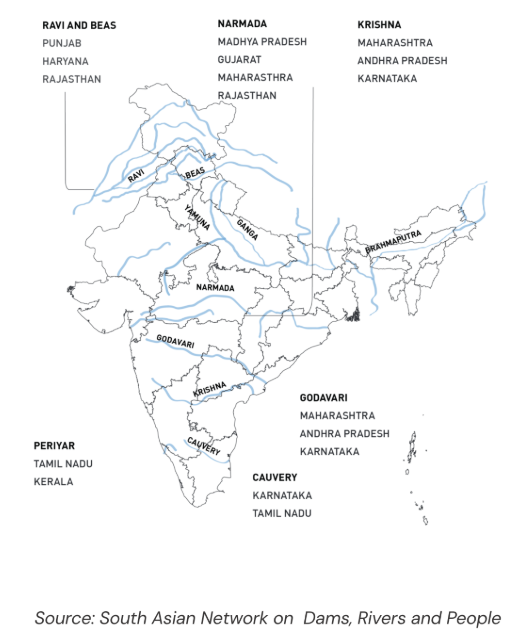

India, with its diverse geography and climate, has numerous river basins that are shared across multiple states (see Fig. 1). However, the management and distribution of water within these shared basins has become a significant source of tension and disputes between Indian states. To resolve these conflicts, the Indian Parliament enacted the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act in 1956, and various Inter-State Water Dispute Tribunals have been established to settle disputes.

There are several river disputes in India centred around the Cauvery(also known as Kaveri) Krishna, and Mandovi Cauvery River dispute, for example, has been a significant source of conflict between the states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, as both seek a larger share of the water. The origins of this dispute trace back to agreements in 1892 and 1924 between the Madras Presidency and the Kingdom of Mysore. These agreements are now outdated due to population growth and changing agricultural needs. This conflict has repeatedly resulted in riots and road blockades, endangering civilian lives and requiring significant security deployments. Therefore, these inter-state water disputes in India present more than just a governance challenge; they affect internal stability and, by extension, national security.

Fig 1: River map of India highlighting Inter-State rivers and disputes

Additionally, the 2023 Global Study on Homicide highlighted that water disputes are a major cause of interpersonal violence in India. The study emphasised the impact of water crisis on societal stability as one in five murders are linked to conflicts over water access. Beyond interpersonal violence, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported 793 water-related disputes and protests in 11 states in 2019 alone. These incidents are warning signs of deeper instability if the crisis remains unaddressed.

Food security at risk

India ranks among the world’s top crop producers, and more than half of its population relies on agriculture for their livelihoods. As the backbone of India’s economy, the agricultural sector has been the hardest hit by the water crisis, directly threatening India’s food security. Approximately 80 per cent of India’s freshwater is consumed in agricultural practices, making it a major contributor to the crisis and one of the most deeply affected sectors. Moreover, India is one of the largest consumers of groundwater in the world. Over the past 50 years, the country’s groundwater usage has risen dramatically by 500%. This can be explained by the policies implemented during the Green Revolution, promoting water-intensive crops like rice and wheat that have depleted aquifers over the years. These policies, which were necessary to address food security in the 1960s, are no longer sustainable. They have inadvertently locked millions of farmers into unsustainable water usage practices, exacerbating the crisis and threatening both food and water security.

The Water-Energy Nexus and Its Economic Impact

Another area of concern is India’s energy sector, as both hydro and thermal power plants depend on water. 70% of India’s electricity is provided by thermal power plants, which rely on freshwater for cooling. From 2017 to 2021, water shortages caused energy losses of 8.2 terawatt-hours, which is enough to light up 1.5 million homes for five years. Between 2013 and 2016, 14 of India’s major thermal utilities were forced to shut down due to water shortages. These disruptions highlight the vulnerabilities in the water-energy nexus, directly impacting India’s economic growth. Even Moody’s ratings have warned that India’s worsening water crisis is a significant threat to the country’s economic stability.

Hydro Diplomacy and Regional Security

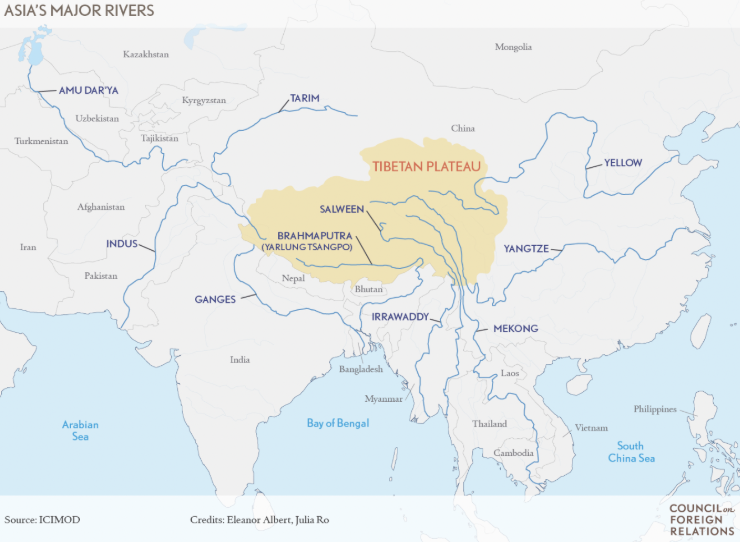

The former president of the World Bank once stated that wars in the 21st century will be fought on water. India’s water crisis is not confined within its borders; rather, cross-border water conflicts are a major contention in the region, affecting India and its neighbours alike. Shared rivers like the Brahmaputra and the Indus (see Fig. 2) represent potential flashpoints with countries such as China and Pakistan, already sources of significant security concerns.

Figure 2: Major river systems originating from the Tibetan Plateau

The recent Pahalgam terror attack killed 26 civilians in Jammu and Kashmir. Following this, India launched Operation Sindoor, and suspended the 65-year-old Indus Water Treaty in response to Pakistan’s cross-border terrorism. The treaty has survived all past conflicts with Pakistan, but this suspension indicates a shift in the terms of engagement with Pakistan, as the mutual trust and goodwill have been eroded. The suspension has not had serious short-term consequences, as disrupting water flow to Pakistan would require years of infrastructure development. In response to this, China, Pakistan’s strategic ally, has expedited the building of the Mohmand dam as part of its dam diplomacy. Pakistan has also responded by suggesting that China could take similar actions against India.

China has emerged as a hydro hegemonic power in South and Southeast Asia, controlling the Tibetan Plateau, the source of major river systems. The new Medog Dam on the Brahmaputra River, considered the lifeline of Northeast India, has heightened New Delhi’s concerns over the possibility of Beijing weaponising its power to control water flow during conflicts. China, India, Bhutan, and Bangladesh have not signed the United Nations Convention on the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses, which makes the situation even more critical. Furthermore, China and India lack a bilateral treaty for sharing transboundary water resources. They primarily rely on non-binding agreements like Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) and joint statements to manage these watercourses. This poses a significant challenge to shared governance and confidence-building in the Brahmaputra River basin.

Therefore, with climate change, growing water scarcity, and prevailing geopolitical instability in the region, the potential for conflicts exists between these nuclear powers and other downstream countries. This impacts the peace and stability in the region and poses a significant threat to India’s national security.

Reconceptualising Water as a Matter of National Security

The Indian government has recognised the severity of the water crisis. Therefore, in May 2019, it established the Ministry of Jal Shakti. This ministry is responsible for national water policies and water resource management nationwide. Several initiatives were launched addressing the growing water crisis – the Jal Jeevan Mission (which aims to provide piped water to every household by 2024), the Atal Bhujal Yojana (for sustainable groundwater management), and Mission Amrit Sarovar (to conserve water by revitalising 75 water bodies in each district) along with other initiatives. Yet, despite some progress, the challenge remains because of the fragmented institutional framework and bureaucratic governance.

Meanwhile, India’s emerging water-tech ecosystem is stepping up. Startups like Uravu Labs, WEGoT, and Swajal are innovating with atmospheric water generation, smart metering, and solar-powered purification. These breakthroughs signal a powerful opportunity for public-private partnerships to make water systems smarter, more efficient, and more resilient.

To achieve its ambitions of becoming a $10 trillion economy and a global power, India needs a holistic, interdisciplinary approach that treats water not merely as a developmental or environmental concern but as a strategic asset. This approach must be reflected not just in rhetoric but in strategy, planning, and robust institutional design. With increasing climate-induced instability, escalating cross-border tensions, and the growing weaponisation of water resources, water must be viewed as central to India’s national security strategy. Addressing this crisis with the same urgency as other traditional internal and external security challenges is crucial. In the 21st century, water is power, water is peace, and water is security.