Authors: Pravar Petkar, Head of Strengthening Democracy Desk; Amy Wonnacott, Research Intern; Zoe Neiman, Research Intern

The UK-India Free Trade Agreement (FTA), agreed yesterday after years of negotiation, marks a critical moment in the evolving relationship between the two countries. With India poised to become the world’s third-largest economy by the end of the decade, and its middle class expected to reach 60 million by 2030, and 250 million by 2050, the agreement provides the UK with preferential access to one of the fastest-growing consumer markets. By 2035, Indian demand for imports is projected to exceed £1.4 trillion, offering vast opportunities for British exporters and service providers. The economic benefits for both countries could be significant.

£ billion estimate, applied to 2040 predications | Percentage change | |

Change in UK GDP | + £4.8 billion | +0.1% |

Change in UK exports to India | + £15.7 billion | +59.4% |

Change in UK imports from India | + £9.8 billion | +25.0% |

Change in total trade between the UK and India | +£25.5 billion | +38.8% |

Source: DBT Modelling

Sectors Covered by the Agreement

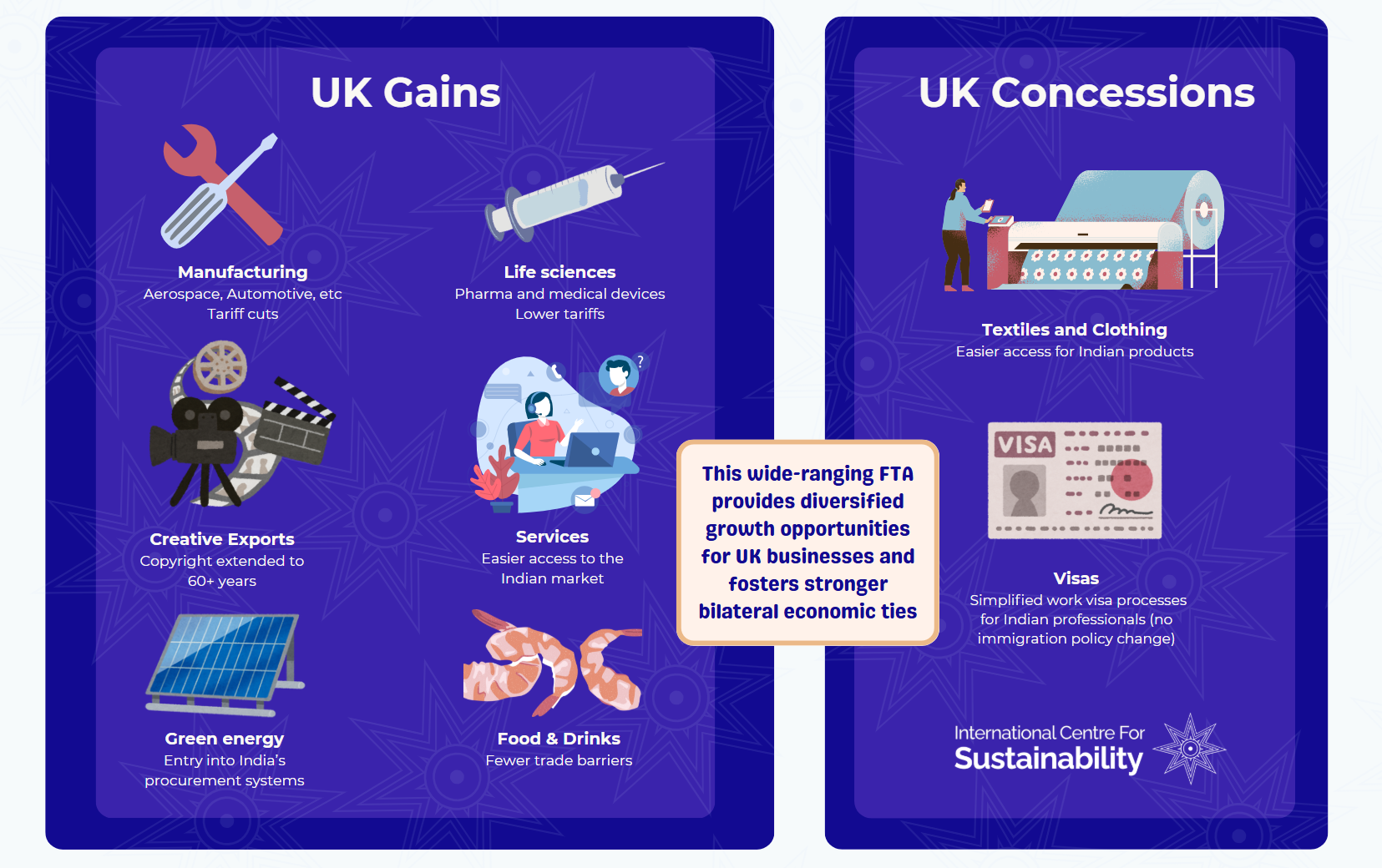

The FTA spans a broad range of sectors, offering benefits for both countries.

Tariff Reductions

The tariff reductions secured under the deal are among the most generous India has ever agreed to. Indian tariffs on 90% of UK export lines will be reduced, with 85% going tariff-free within a decade. Based on 2022 trade figures, Indian tariff reductions will save UK exporters £400 million in the first year and £900 million annually in ten years. As high priority trade partners, the UK and Indian governments have set an ambitious target of $1 trillion export growth by 2030, facilitated by the mutual concessions in this FTA.

Goods | Previous tariff | FTA tariff |

India Tariffs on UK | ||

Alcohol | 150% | 75%, 40% over decade |

Automotive | 100% | 10%, quota system |

Cosmetics | 10-20% | 0% |

Source: GOV.uk

Social security benefits

Alongside the FTA, the UK and India have “agreed to negotiate” a reciprocal agreement on social security contributions. This would ensure that British workers seconded to India and Indian workers seconded to the UK need only pay National Insurance and its Indian equivalent, a contribution to the Employees’ Provident Fund, in their home country, avoiding ‘double contribution’. The proposed Double Contributions Convention also extends the period of time for which temporary workers contribute to social security in their home country from 1 to 3 years. This has been criticised in the UK for ‘undercutting’ British workers. However, according to the UK’s Business Secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, this applies only to seconded workers, and mirrors agreements the UK has with the EU, Switzerland, Japan, Chile and South Korea. The workers affected would not gain new rights to access benefits, and Indian workers would still have to pay the NHS surcharge in the UK, which totals £1035 per year. This will not incentivise British businesses to recruit Indian workers over British ones, but does give Indian businesses a competitive advantage over other countries with which the UK lacks such an agreement.

Higher education and the legal sector

There is speculation that the FTA could present an opportunity for British and Indian businesses to pioneer new commercial ventures, including in AI and cybersecurity, bringing benefits to sectors such as higher education. This is a developing market in India: the University of Southampton opened its Delhi campus in July 2025, Coventry University will open in GIFT City (Gujarat International Finance-Tech City) in 2026, and the University of York plans to open a campus in Mumbai. Though the FTA may encourage further transnational educational initiatives, it has no specific reference either to this, or the greater availability of student visas for Indian international students to the UK.

The legal sector is another area of potential UK-India collaboration. It was announced in January 2025 that English-qualified lawyers could register to practice permanently in India, liberalising India’s legal market. Yet this has faced pushback from the Society of Indian Law Firms, and concrete progress remains to be seen. The FTA includes no direct reference to the legal sector, which the Law Society views as a “missed opportunity”.

Why is this good for the UK and India?

This FTA is the most economically significant bilateral trade deal the UK has made since leaving the EU. The forecasted economic benefits for the UK are significant, contributing to the government’s Plan for Change. Modelling by the UK Department of Business and Trade predicts the deal to add £4.8 billion to the UK economy, and increase wages by £2.2 billion each year.

For India, the reduction of tariffs in key sectors such as green energy, medical and life sciences will be crucial for its growth trajectory. India’s energy strategy remains reliant on coal, but aims for net-zero emissions by 2070 and has set ambitious targets towards solar and renewables. Facilitating trade in renewable energy equipment will support India’s transition, alongside the opportunity to use expertise from UK businesses and government procurement. Healthcare is one of India’s largest sectors and is projected to reach $194 billion by 2032. Lowering tariffs on British exports of medical goods will facilitate this rapid growth, improving care quality and reducing the cost of private healthcare.

Importantly, the FTA provides a platform from which other deals could be negotiated. Proposals for a follow-up Investment Treaty have been discussed, and the FTA offers the opportunity to deepen economic and strategic ties between two powerful economies, while supporting both manufacturers and consumers and UK presence in the Indo-Pacific region.