From Beijing to Delhi: Britain’s New Bet

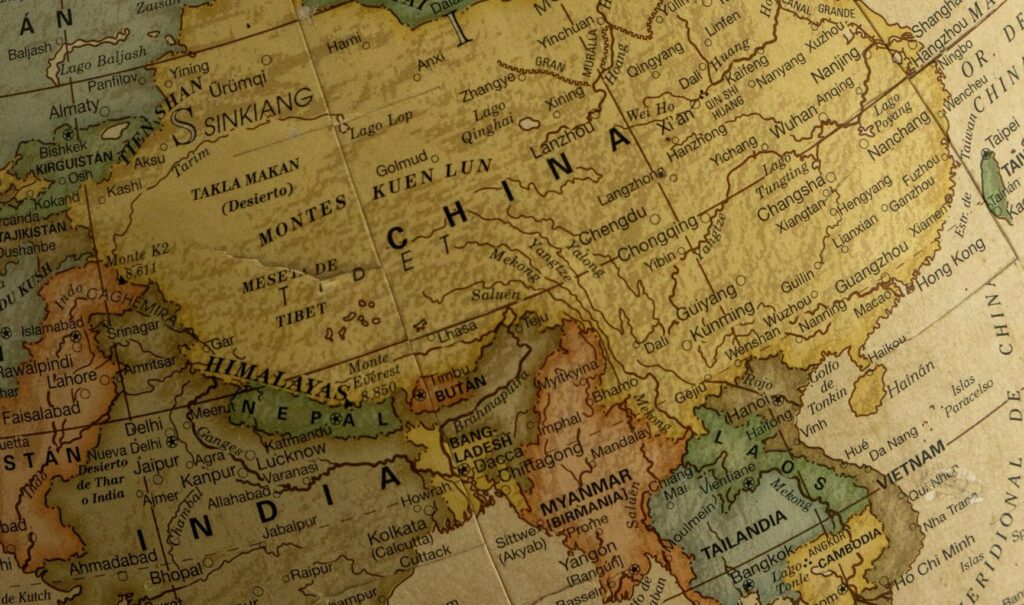

Author: Sachin Nandha, DIrector-General Last week, Britain’s Prime Minister Keir Starmer made his first state visit to India, arriving with a 125-strong delegation of business, academic, and cultural leaders. The official reason was to advance the recently signed UK–India Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). The deeper reality, however, was a decisive tilt in Britain’s foreign economic orientation away from the embattled Sino-centric axis of previous years and toward a future in which Delhi may matter more than Beijing. In July 2025, the United Kingdom and India signed their long-anticipated free trade agreement after three years of negotiation. The deal promises to eliminate tariffs on more than 90 percent of UK exports to India, including cosmetics, clothing, and Scotch whisky, and to offer zero duty on 99 percent of Indian exports to the UK. India will also reduce duties on cars, currently above 100 percent, to 10 percent under a quota, while providing enhanced access to procurement and services sectors (Reuters, 23 July 2025). The two countries also agreed to reset a Joint Economic and Trade Committee (JETCO) to manage implementation and launched new cooperative initiatives in innovation, connectivity, and artificial intelligence (Government of the United Kingdom, 9 October 2025). What Britain hopes to gain is clear. Access to India’s fast-growing market projected to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2028, is the sort of expansion that post-Brexit Britain urgently needs (Reuters, 7 October 2025). The agreement is projected to generate around 6,900 new UK jobs across sectors such as engineering, creative industries, and technology. The deal also strengthens Britain’s credibility in South Asia’s strategic landscape, a valuable asset at a time when global power rivalries are sharpening. India’s gains are equally significant. Indian exporters of textiles, agricultural goods, and pharmaceuticals will now enjoy much greater access to UK markets, often duty free (Reuters, 7 October 2025). Delhi also secured commitments for nine UK universities to open campuses in India and for increased collaboration in technology and artificial intelligence (NDTV, “India–UK Trade Pact to Boost MSMEs, Create Jobs,” 2025). In addition, a new mobility scheme will allow 3,000 Indians and 3,000 Britons to live and work in each other’s countries for up to two years. Politically, the deal enhances India’s stature as a preferred partner of a major Western democracy. However, the partnership is not without its difficulties. India failed to secure an exemption from Britain’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, meaning that high-emission exports may face additional cost burdens (Reuters, 23 July 2025). A bilateral investment treaty remains unresolved, and key issues such as rules of origin, liberalisation of financial services, and certain visa provisions are still under negotiation or only partially settled. Furthermore, British firms face stiff competition from Chinese, Korean, and ASEAN rivals that benefit from greater state support and more favourable regulatory regimes. This situation invites comparison with Britain’s recent China strategy. Over the past decade, the UK’s relationship with China has evolved from enthusiastic engagement to cautious distance. In early 2025, the United Kingdom prepared to resume trade talks with China for the first time in seven years, reviving the Joint Economic and Trade Commission (JETCO) that had been dormant since 2018 (Government of the United Kingdom, 2025). In January 2025, during the UK–China Economic and Financial Dialogue, Beijing agreed to re-list UK pork processors, ease access for legal services, grant better export certification for wool, andopen doors for Scotch whisky labelling (Government of the United Kingdom, “2025 UK–China Economic and Financial Dialogue Fact Sheet”). Despite these gestures, the numbers tell a less flattering story. According to the UK Department for Business and Trade, UK goods exports to China fell by 25.7 percent in the year to the first quarter of 2025, while imports from China rose by more than 5 percent, resulting in a trade deficit of £42 billion (UK Government, “China Trade and Investment Factsheet,” 19 September 2025). Britain’s approach to China has become a balancing act between commercial opportunity and security risk, as noted by analysts at Chatham House (“What the UK Must Get Right in its China Strategy,” July 2025). It is therefore no coincidence that Britain now courts India with enthusiasm. India’s democratic governance and relatively lower geopolitical risk make it a safer bet than Beijing’s opaque state capitalism. Where China represents an enormous but fraught dependency, India represents a promising partnership built on aspiration and mutual political legitimacy. Britain is effectively pivoting from a relationship based on dependence toward one based on alignment. Still, the success of this realignment depends on consistent implementation. Britain must ensure that Indian exporters do not simply displace other partners, and that small and medium-sized British enterprises not only large corporations benefit from the trade deal. India, for its part, must resist the temptation to reintroduce protectionist measures that could stall liberalisation. In summary, the Starmer mission to Mumbai symbolised ambition more than certainty. The new trade pact could yet become the crown jewel of Britain’s post-Brexit trade policy—or another well-intentioned treaty that fades under the weight of bureaucracy. For now, London and Delhi walk forward hand in hand, in a world where China still looms large, but no longer dictates the direction of travel. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Reuters (23 July 2025). Britain and India sign landmark free trade pact during Modi visit. https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/britain-india-sign-landmark-free-trade-pact-during-modi-visit-2025-07-23 Reuters (7 October 2025). UK PM Starmer visits India to build business ties after clinching trade deal. Government of the United Kingdom (9 October 2025). India–UK Joint Statement. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/india-uk-joint-statement-9-october-2025 NDTV (2025). India–UK Trade Pact to Boost MSMEs, Create Jobs. Wikipedia. India–United Kingdom Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement. Government of the United Kingdom (2025). UK–China Economic and Financial Dialogue Fact Sheet. UK Government (19 September 2025). China Trade and Investment Factsheet. Chatham House (July 2025). What the UK Must Get Right in its China Strategy.

From Beijing to Delhi: Britain’s New Bet Read More »